Everywhere, All at Once

And what a start to the year!

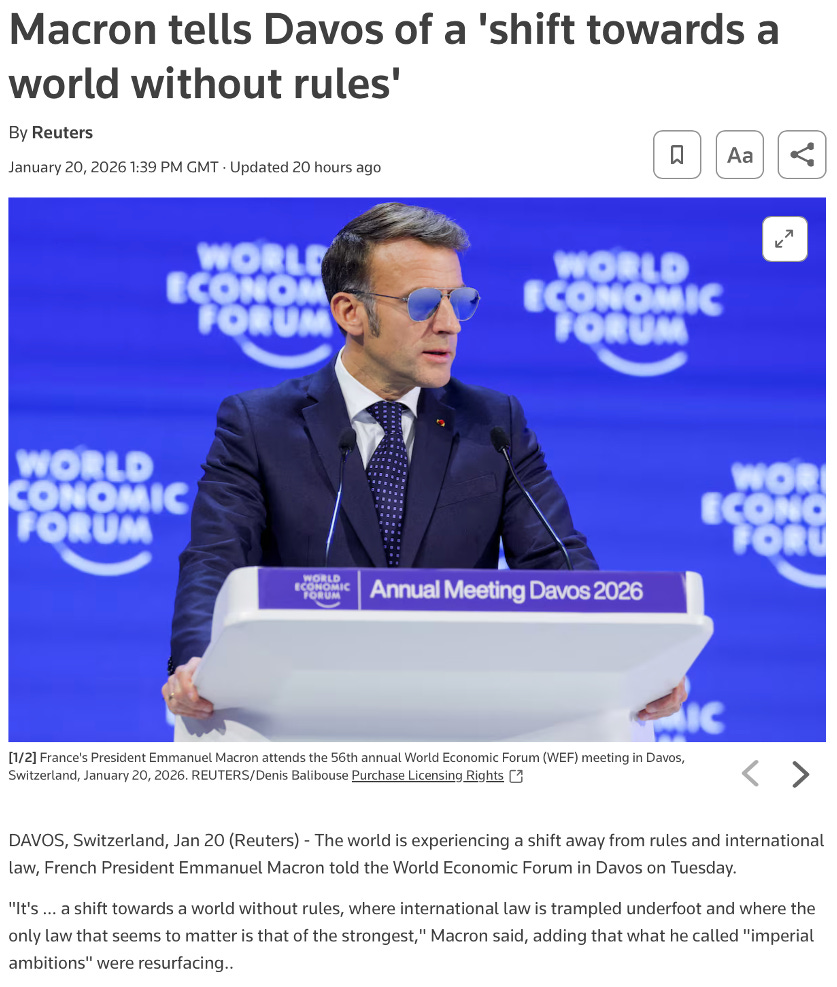

In barely a few weeks, Donald Trump has signed a memorandum directing the United States to withdraw from 66 international organizations deemed contrary to U.S. interests.

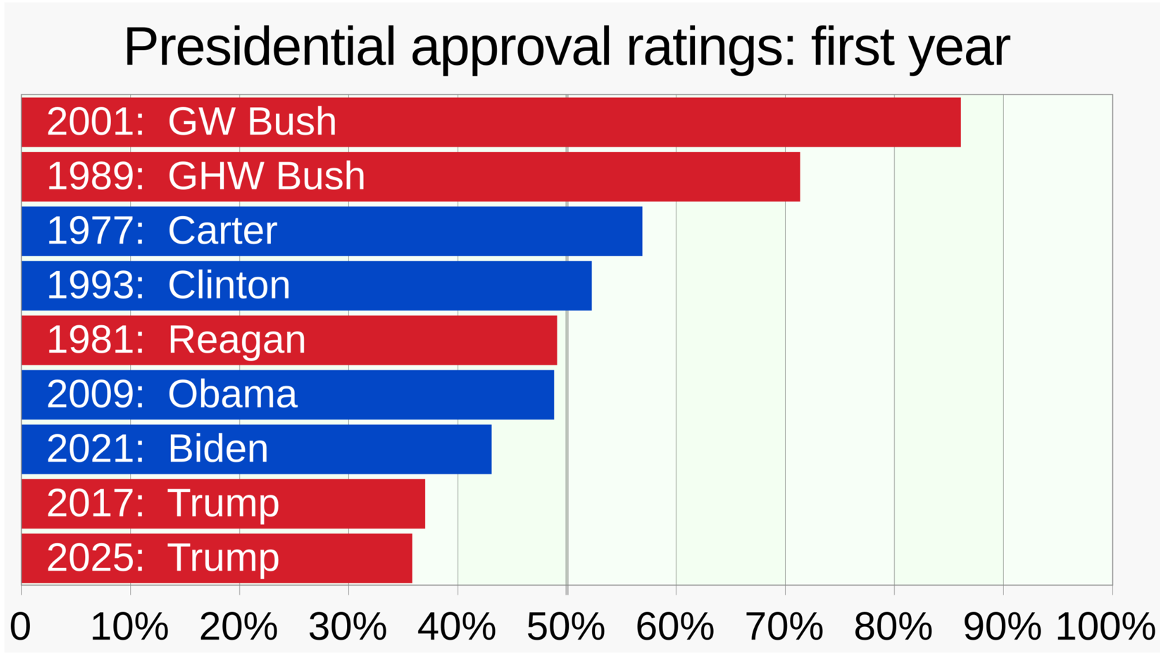

Federal prosecutors have opened a criminal investigation into Fed Chair Jerome Powell, in a development that has reignited the debate around the Fed’s independence.

The United States has also captured Venezuela’s leader, Nicolás Maduro, after what Reuters described as a “large scale” operation, with Trump stating the U.S. would “run” Venezuela until there could be a “safe” transition.

Meanwhile, tensions with Iran have escalated sharply, with the White House leaning into a mix of coercive trade threats and geopolitical brinkmanship.

And then there is Greenland... a story that still sounds surreal to most people yet has already spilled over into transatlantic relations through explicit tariff pressure.

If you consume these headlines one by one, they can feel like a chaotic collage.

A foreign policy crisis here, an institutional clash there, a trade threat somewhere else.

Unrelated. Random. Noise.

But that is not how we see it...

To us, these events are not disconnected at all.

They align perfectly with the Fourth Turning framework1 and the big generational cycles we’ve been writing about since our inaugural issue.

In fact, they look almost textbook when viewed through that lens: institutions being stress-tested simultaneously, legitimacy being challenged, alliances being renegotiated, and power being reasserted in ways that would have been politically unthinkable just a few years ago.

You might also like reading:

So, in this issue, we will do what we always do at Alpha Tier: step back from the noise and map it into a coherent model.

First, we’ll provide an update to our generational playbook... what has changed, what has accelerated, and, most importantly, where we sit right now inside the cycle.

Then we’ll bring in a much shorter, but no less important cycle that, in 2026, is synching perfectly with the Fourth Turning: the Presidential Cycle.

The Presidential Cycle is a market timing framework that tracks how U.S. stocks have tended to behave over the four-year presidential term. In broad strokes, it observes that returns are often weakest in the second year (the midterm election year, when uncertainty peaks and political incentives shift), and strongest in the third year, when policy typically turns more supportive ahead of the next presidential election.

You see, 2026 is a midterm election year in the United States.

And midterms are rarely polite.

They are often the moment when incentives become raw, when political capital is either defended aggressively or lost decisively.

In other words, it’s the kind of calendar year where the pressure to “do something big” can overwhelm the instinct to “keep things stable.”

We’ll share our take on how these early-2026 events fit into that make-or-break setup for Trump... and why the political cycle is amplifying the generational one.

And of course, we’ll connect all of this back to what matters most: financial markets and the positioning of our Model Portfolio.

The year has started extremely well for us.

That’s the good news. But strong starts can be deceptive in Crisis eras. So, we’ll comb through the recent model portfolio additions in both Tier One and Tier Two, test whether they also make sense for Alpha Tier, and assess what this macro-political regime implies for opportunity and risk.

We’ll end with what may be the most important exercise of all: is it time to buy downside protection through our options overlay strategy, especially when performance is already strong and complacency is easiest?

Discover in the pages ahead.

When the Rulebook Breaks

2026 is a midterm election year.

And that matters far more than most investors realize. Midterms are the political equivalent of a stress test. They take place halfway through a president’s term and determine control of Congress.

In today’s hyper-polarized world, they decide whether a president governs with momentum or spends the rest of the term boxed in, investigated, and legislatively paralyzed.

Lose them badly, and the second half of a presidency becomes little more than a prolonged exercise in damage control.

For Donald Trump, the stakes could not be higher.

A hostile Congress would mean blocked agendas, aggressive oversight, subpoena power wielded freely, and a narrative of political weakness that markets and allies alike understand instinctively.

In midterm years, presidents do not merely campaign for their party, they campaign for their own survival as effective leaders.

Now layer that reality onto what the data is already telling us.

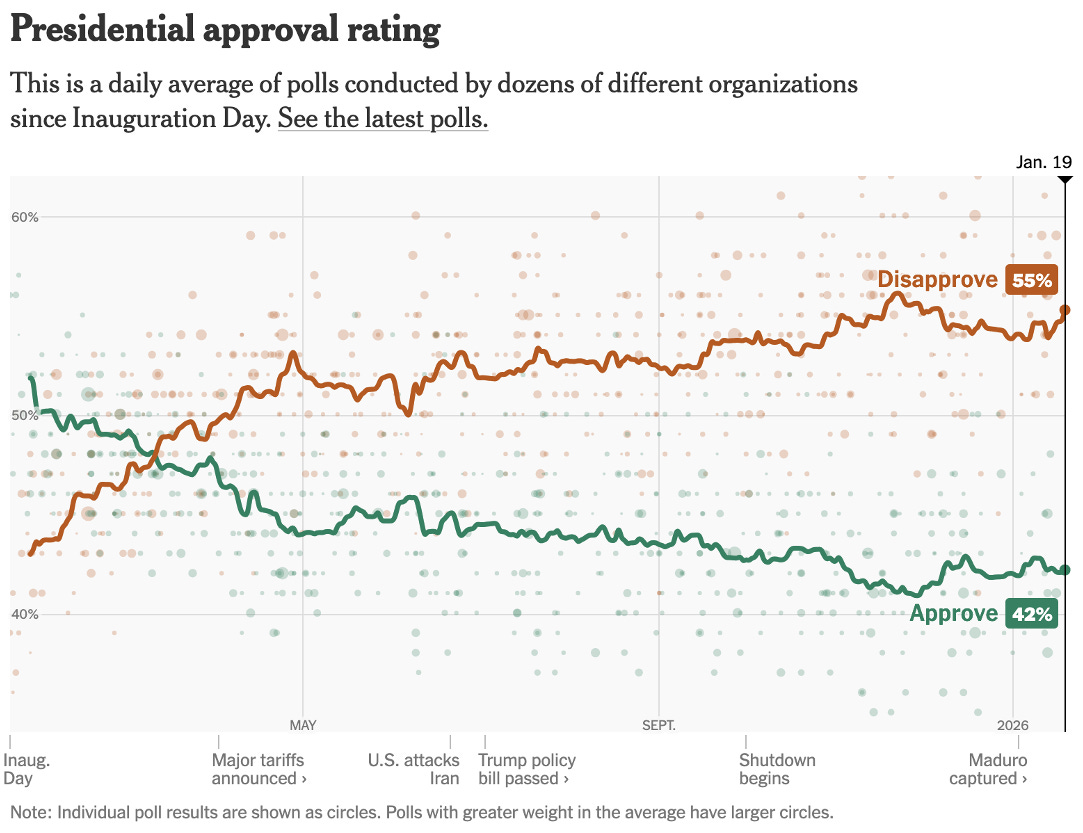

As you can see in the chart on the last page, Trump’s approval rating is not only low - it has been trending lower for months.

This is not a one-off bad print or a single outlier poll. The deterioration is persistent.

And it’s not confined to one pollster or one political camp.

Across a broad range of surveys (Reuters/Ipsos, AP-NORC, Marist, and others) the message is remarkably consistent.

Approval hovering around the low 40s.

Disapproval entrenched well above the mid-50s.

Weak readings not just on one issue, but across the board: the economy, foreign policy, institutional trust.

In other words, these are not “noisy” polls. They are reinforcing signals.

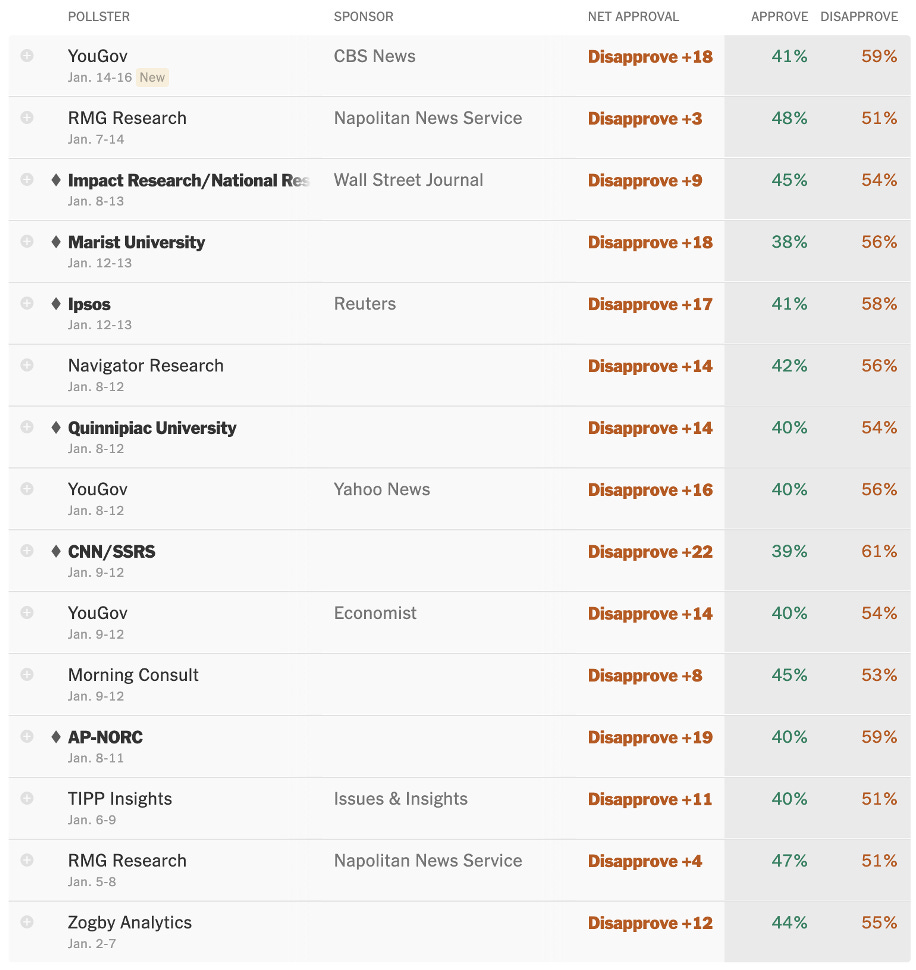

More importantly, Trump now finds himself with one of the weakest approval ratings one year into a presidency in generations.

Historically, this is the point in the cycle when presidents still enjoy residual goodwill.

The honeymoon may be over, but the benefit of the doubt usually remains.

It hasn’t this time.

And this is where things get interesting. Because when a president enters a midterm year with falling approval, shrinking political capital, and an increasingly hostile electorate, the incentive structure changes...

Subtly at first. Then all at once.

Caution gives way to urgency.

Incrementalism gives way to shock. And stability, especially institutional stability, becomes negotiable.

And while this is Donald Trump we’re talking about, this is not primarily about personality. It is, above all, about cycle dynamics.

Low approval in a midterm year doesn’t encourage restraint. It encourages action.

Big action. Loud action. Action that reshapes narratives, reasserts authority, and forces everyone: voters, markets, allies, and adversaries, to react.

And when you place that political cycle inside a Fourth Turning, where institutions are already fragile and legitimacy is already contested, the result is exactly what we’re witnessing now: multiple “Trumpquakes” hitting simultaneously.

Not randomly. Not emotionally.

But structurally.

It’s in this context that we need to unpack the significance of the barrage of events we’ve witnessed over the past three weeks.

Let’s start on the domestic front.

We’ve written extensively about the structural need for lower interest rates in the United States to accommodate the rollover of gargantuan amounts of government debt.

That reality hasn’t changed. If anything, it has become more pressing.

And now, the Trump Administration has taken its confrontation with monetary authority to an entirely new level.

By allowing federal prosecutors to pursue criminal charges against Fed Chair Jerome Powell, the White House has crossed a line that markets understand instinctively.

We will not expand here on the merits (or lack thereof) of the accusations themselves. That’s not the point.

What matters is how markets have interpreted this move.

Correctly, in our view, it has been read as yet another direct attack on the independence of the Federal Reserve.

And more broadly, as one more piece of evidence that the United States is operating deep inside a Fiscal Dominance regime, where monetary policy is no longer free to prioritize inflation control or financial stability, but is increasingly subordinated to the political and fiscal imperative of servicing the debt.

But when it comes to interest rates, Donald Trump has not stopped at the Fed.

If rates won’t come down fast enough through monetary policy, he appears determined to push them lower by any means necessary , and not just for the U.S. Treasury, but for his political base as well.

Two market interventions stand out.

The first is the order for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to buy back roughly $200 billion in mortgages.

The objective here is not subtle.

It is to drive mortgage rates lower, quickly, and visibly.

In a country where housing affordability has become a political fault line, cheaper mortgages translate directly into political relief.

The second is even more explicit.

Trump has floated the idea of capping credit card interest rates at 10%.

Once again, we won’t dwell on the merits (or the long-term consequences) of such a blunt intervention in the credit market.

That debate misses the signal.

Here it is, in plain sight.

A sitting president, heading into a midterm election year, with approval ratings sliding, is attempting to directly lower interest bills for American households.

Lower mortgage payments.

Lower credit card balances.

Lower monthly stress.

And we’re supposed to believe this is accidental?

Hardly.

This is what Crisis-era incentives look like in practice.

When political capital is eroding and the clock is ticking, orthodoxy gives way to urgency. Market neutrality becomes optional.

And financial repression (overt or covert) starts to look like a feature, not a bug.

Coincidence? We don’t think so.

Advancing to the foreign front, Trump’s moves have been even more brash and disruptive.

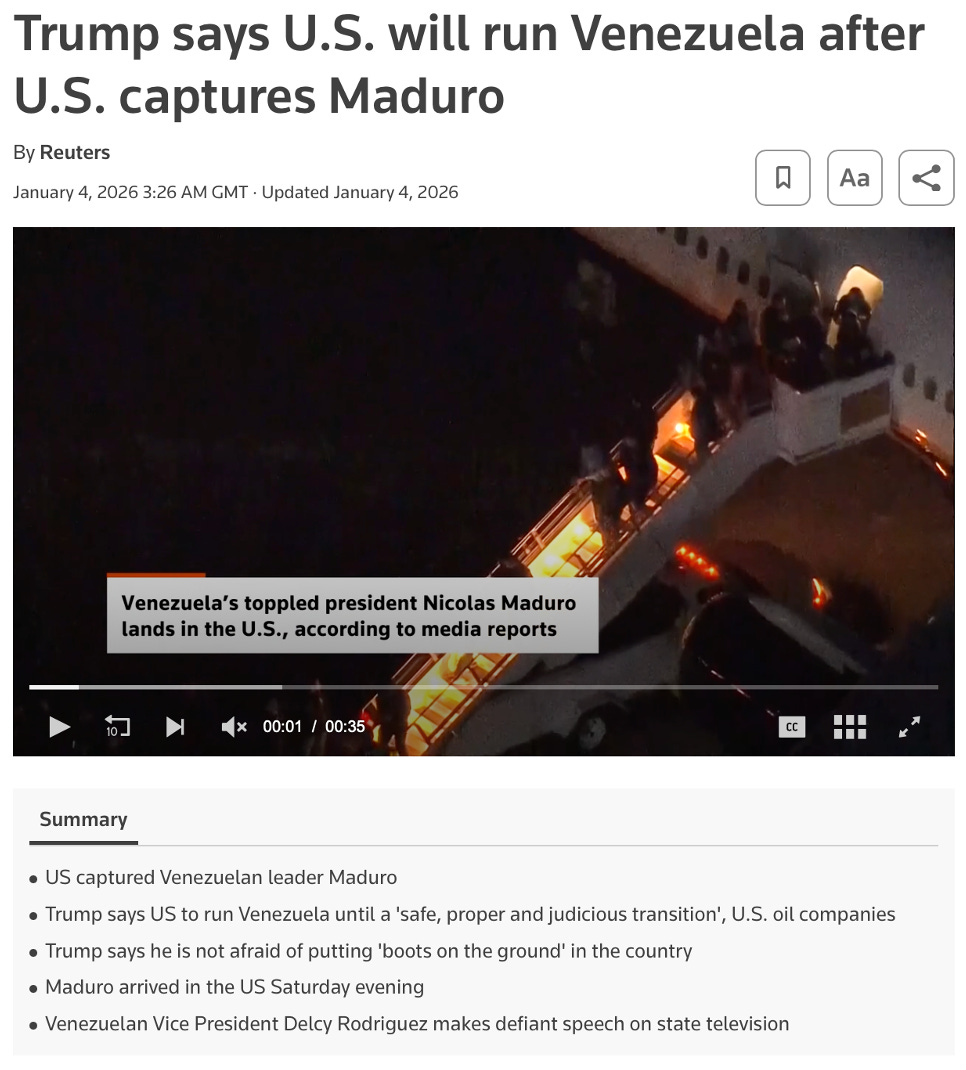

On Venezuela, the U.S. conducted what was described as a large-scale operation that resulted in the capture of Nicolás Maduro, an extraordinary event in hemispheric geopolitics.

Trump publicly stated that the U.S. would “run the country” until a safe transition could be arranged, and Trump-aligned forces have signaled control over oil flows and governance mechanisms in the interim government structures.

This was not simply military theatre... it has direct implications for oil supply, refining, and trading relationships in a world still sensitive to energy price dynamics, and thus for consumer prices back home.

Meanwhile, in the Middle East, Trump’s rhetoric and actions around Iran have once again pushed geopolitical tensions higher.

From explicit threats of military response, to public encouragement of protest movements, to proposals for sweeping economic penalties tied to Iran’s regional behavior, the signal has been unmistakable.

Markets and diplomats alike have taken notice, pricing in higher risk premia and quietly recalibrating alliances and contingency plans.

Taken in isolation, episodes like these are often dismissed as impulsive or purely theatrical. Another headline. Another escalation. Another reversal. But viewed through the lens we’ve been refining since our inaugural issue... a very different picture emerges.

What we see instead is pattern consistency.

Long before 2026 began, we described Trump’s agenda as fundamentally mercantilist and rooted in realpolitik based on strength and leverage; not in the rules-based, institution-centric order that emerged after World War II, at the very beginning of the generational cycle now in its final innings.

We argued that his approach would not resemble classical isolationism, but rather a form of confrontation-driven negotiation, where pressure, asymmetry, and material interests take precedence over process, norms, or multilateral consensus.

And crucially, this is precisely how Fourth Turnings unfold.

Crisis eras are not about reforming the old rulebook.

They are about replacing it.

They are defined by the open defiance of institutions that no longer command legitimacy, by the rejection of constraints that belong to a fading order, and by the reassertion of power in its most tangible forms: economic, military, and geopolitical.

Seen through that prism, Trump’s actions toward Iran are not aberrations.

They are expressions of a deeper cycle at work. The old post-war architecture is being stress tested, challenged, and, in many cases, deliberately bypassed.

Not out of caprice, but because Crisis eras demand resolution, not accommodation.

And that is the common thread running through these “Trumpquakes.”

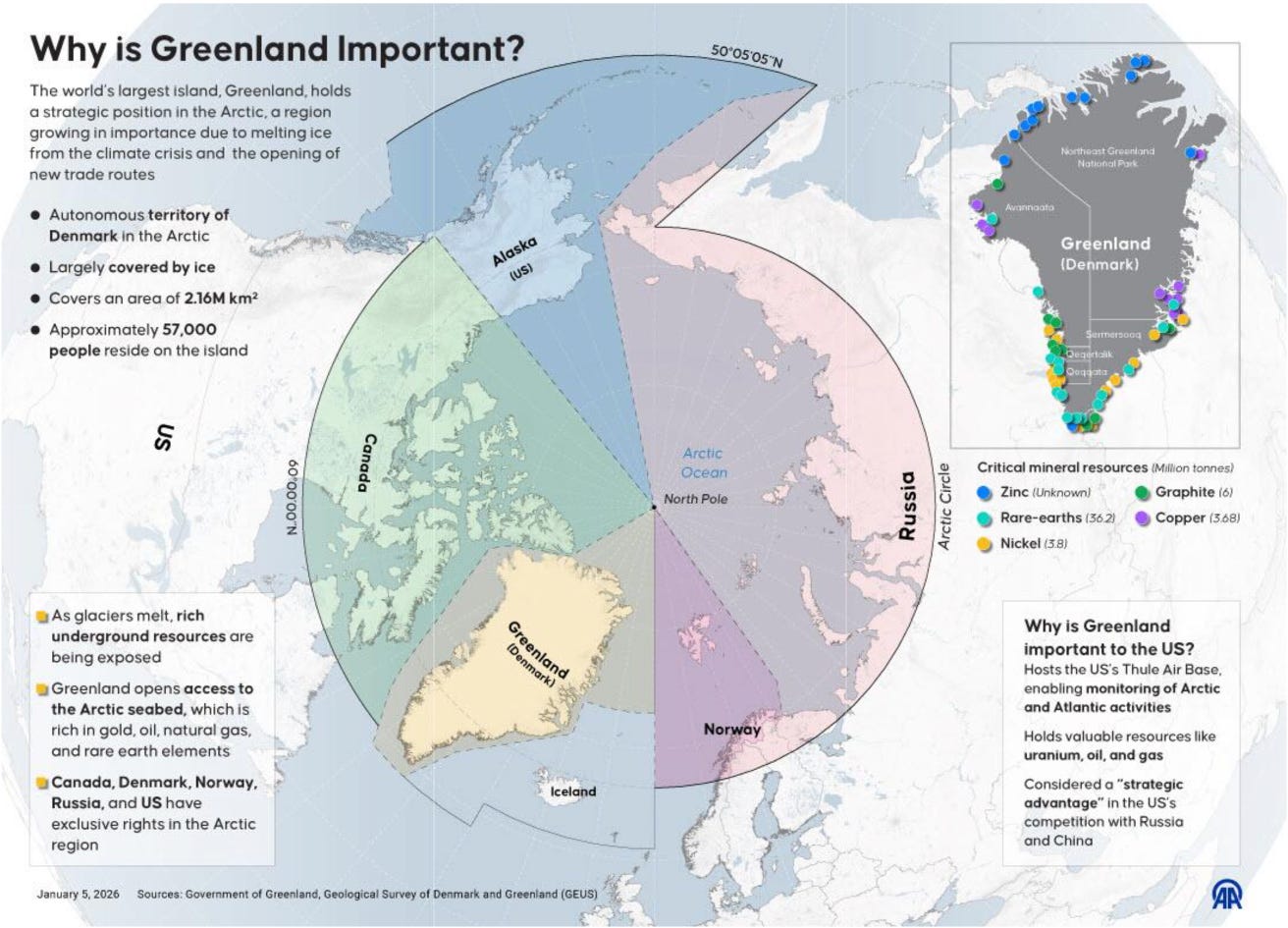

Why is Greenland Important?

Now, it is one thing to wage geopolitical friction around Venezuela and Iran.

It is quite another to make a strategic landmass itself the centerpiece of an asserted national project.

Yet that is precisely how Greenland has emerged... not as a peripheral afterthought, but as the clearest signal of a mercantilist, realpolitik agenda intersecting with the Crisis era logic we’ve described.

Greenland’s importance is not subjective or rhetorical.

The island sits at the crossroads between North America, Europe, and the Arctic, a locale that has shaped global security thinking for decades.

Its position gives it direct visibility over the GIUK Gap (the sea and air approaches between Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom) long recognized as a chokepoint in any conflict involving the North Atlantic and Arctic waters.

The U.S. has maintained a presence there for decades, notably at the Pituffik Space Base, which forms a cornerstone of continental missile warning and surveillance capacity.

These are capabilities that cannot simply be replicated elsewhere.

Now add two economic dimensions that amplify Greenland’s relevance in an era when power and resources are inseparable:

The emergence of viable Arctic shipping lanes as the polar ice retreats, a transformation that could redraw global logistics patterns by connecting Asia, Europe, and North America through shorter northern routes that bypass traditional chokepoints.

Greenland sits within reach of these new corridors, making it far more than an isolated outpost; it becomes a potential hub in a new era of trans-Arctic trade.The island’s vast mineral wealth, including rare earth elements critical to modern defense and technology systems, as well as iron, copper, nickel and other resource classes coveted for both industrial and military applications.

While development has lagged due to environmental and logistical constraints, melting ice and global competition for inputs give this resource base strategic, not speculative, value.

Viewed from a traditional geopolitical lens, these are reasons for sustained interest.

But the manner in which they are now being pursued reveals something deeper.

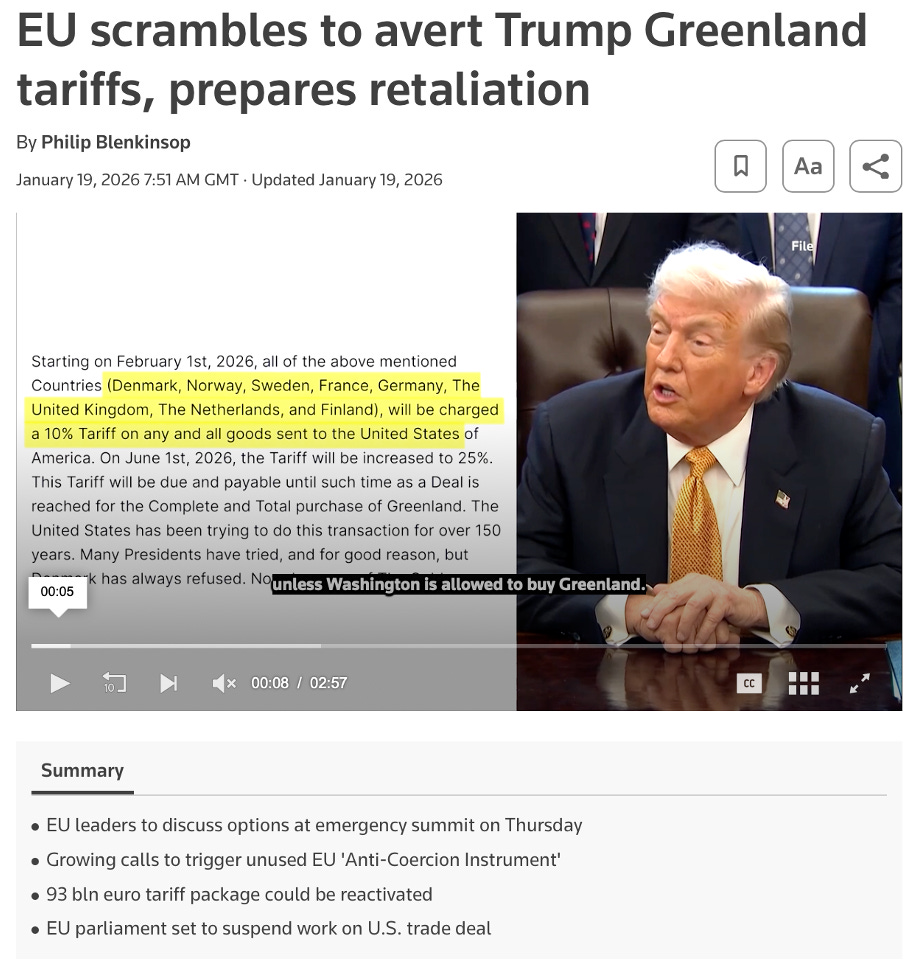

Rather than work through alliance frameworks or multilateral institutions that defined the post-World War II order, the Trump administration has escalated unilateral pressure, threatening tariffs against multiple European nations, openly revisiting ideas of territorial acquisition, and framing U.S. control of Greenland as necessary to “deter adversaries” like Russia and China.

European leaders have responded sharply, warning that a military takeover would threaten NATO’s unity and signaling increased defense commitments in the Arctic, including troop deployments and enhanced NATO activity around the island.

This pack of actions encapsulates the mercantilist realpolitik logic at play: strategic

geography and resources become levers in a negotiation measured not by rules or norms, but by power and leverage.

Greenland is not being pursued because of an abstract interest in sovereignty... it is being pursued because control over strategic routes and resources enhances national position in both geopolitics and global supply chains.

The notion that the U.S. “needs Greenland” to prevent others from gaining a foothold underscores that this isn’t traditional diplomacy, it is raw leverage over geography, routes, and resources.

What makes Greenland especially revealing within the Fourth Turning context is how institutional conventions are being bypassed or strained.

Allies are publicly admonishing the U.S., NATO coherence is being tested, and the island’s own government has stressed its commitment to multilateral defense through NATO rather than unilateral control.

Yet Washington’s posture remains anchored in a negotiating strategy that starts with maximalist claims and uses them to pull the strategic center of gravity toward its interests... whether or not actual sovereignty changes hands.

Seen this way, Greenland is not a quixotic obsession.

Trump’s Negotiation Playbook is simple: start with maximalist, even “unreachable” demands, force the counterparty to react, and then bargain down from an anchored position—often extracting real concessions without ever needing the original endgame.

We’ve been describing this approach since before he took office, which is why we’ve been anticipating these Trumpquakes and positioning around their likely outcomes rather than getting distracted by the headlines.

It is the purest contemporary expression of the very dynamic we have been tracing: a realpolitik-driven push for leverage over rules, set against the backdrop of a global order that is being reconfigured.

It is geographic strategy meeting generational politics... with the cycle pushing leaders toward bold, disruptive action rather than incremental diplomacy.

In the broader sequence of 2026 events, from institutional pressure on the Fed to geopolitical moves in Venezuela and the Middle East, Greenland stands out because it combines economics, defense, resources, and power projection into one unmistakable geopolitical signal: the old post-war framework is giving way, and what emerges in its place will be defined by competition over power, access, and advantage, not by the norms that once governed international relations.

Mainstream headlines are suddenly full of talk about a “New World Order”… but to us, that’s simply the Fourth Turning playbook becoming impossible to ignore: institutions losing legitimacy, power politics replacing rules, and the old post- WWII framework cracking under stress.

Most market watchers are still treating these shifts as isolated shocks — when they’re really the increasingly flagrant pattern of a generational cycle reaching its climax.

Well... this, in a nutshell, is exactly what we should expect from a Fourth Turning as it approaches its climax.

Multiple systems under strain at the same time.

Domestic institutions being openly challenged.

Foreign policy shifting from rules to leverage.

Economic orthodoxy giving way to urgency.

And power, political, monetary, and geopolitical; being asserted more bluntly, more visibly, and with far less regard for the conventions of the fading order.

These dynamics are not anomalies.

They are hard evidence in support of the thesis we’ve been sharing with you since our very first publication.

And it is precisely for this reason that our Model Portfolio has been reacting so strongly.

Not randomly.

Not by luck.

But because many of our core positions are explicitly aligned with these massive macro and generational forces, particularly those assets that tend to come alive when confidence in institutions weakens and the rules of the monetary system begin to bend.

It should come as no surprise, then, that precious metals have been among the most responsive.

Historically, these assets play an increasingly central role during the monetary resets that so often accompany the final stages of Fourth Turnings.

You might also like reading:

They are not simply trades.

They are reflections of regime change... signals that the old monetary architecture is under stress and that trust is migrating away from promises and toward permanence.

Which brings us to the question that matters most at this stage of the cycle: what should we expect from financial markets as the Fourth Turning draws toward its resolution over the next few years?

To answer that properly, there is one essential step.

We must go back to the source.

That means revisiting what the very architect of the Fourth Turning framework, Neil Howe, is saying now... not decades ago, and not in theory, but in light of current events.

In a recent interview, Howe was unusually direct.

His message was not that the Fourth Turning is coming.

It is that we are already deep inside it and that the most unstable phase may still lie ahead. What stood out most was his emphasis on financial markets.

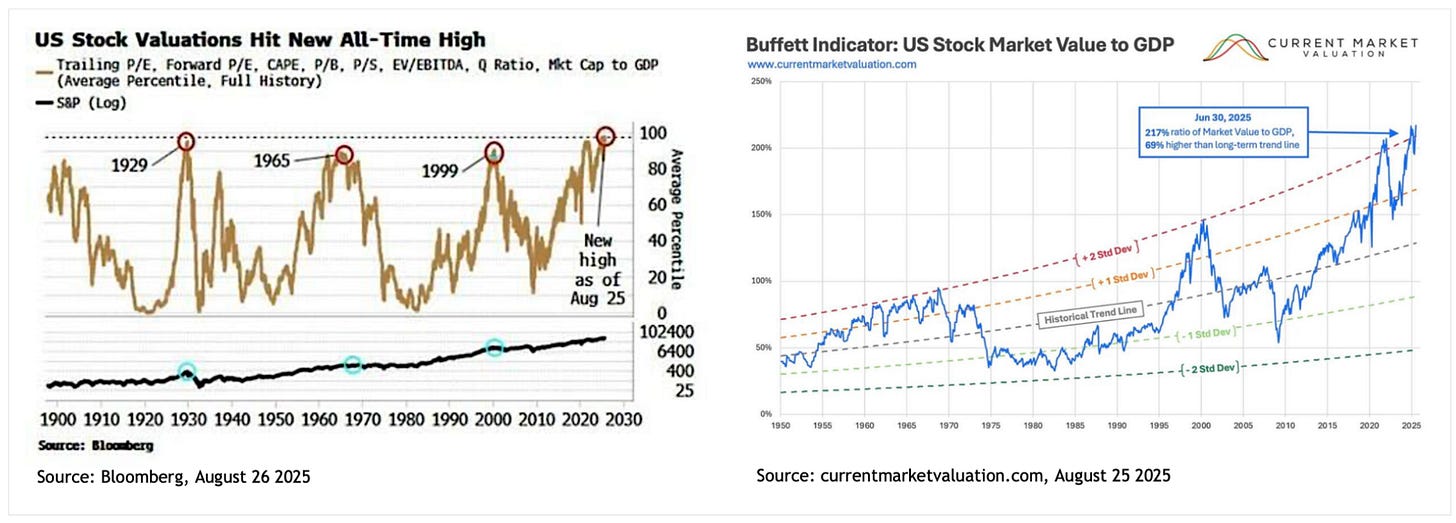

Unlike previous Crisis eras, Howe noted, this Fourth Turning began with asset prices still elevated, balance sheets still stretched, and excesses largely deferred rather than resolved.

That, in his words, makes the adjustment ahead exceptionally dangerous.

In past Fourth Turnings, markets entered the crisis already broken.

This time, they did not...

Howe’s warning was clear: when political pressure, fiscal dominance, and institutional stress collide with unresolved financial excess, markets cease to be a buffer.

They become a catalyst.

Volatility rises.

Correlations shift.

And capital begins to migrate rapidly toward assets perceived as resilient to systemic change.

Yet, consistent with his lifelong work, Howe was not pessimistic about the destination... only about the journey.

Crisis eras are chaotic by design.

They are meant to break what no longer works so that something new can emerge.

Financial turbulence, in this context, is not a failure of the system.

It is part of the mechanism of renewal.

For investors who understand cycles, that distinction is everything.

And it is precisely why positioning, not prediction, becomes the decisive variable as the Fourth Turning moves closer to its end.

For us, this latest interview from Neil Howe (which you can watch on YouTube on Adam Taggart’s Thoughtful Money channel, published on January 5th) comes as no surprise at all.

In fact, it mirrors our own analysis almost point for point.

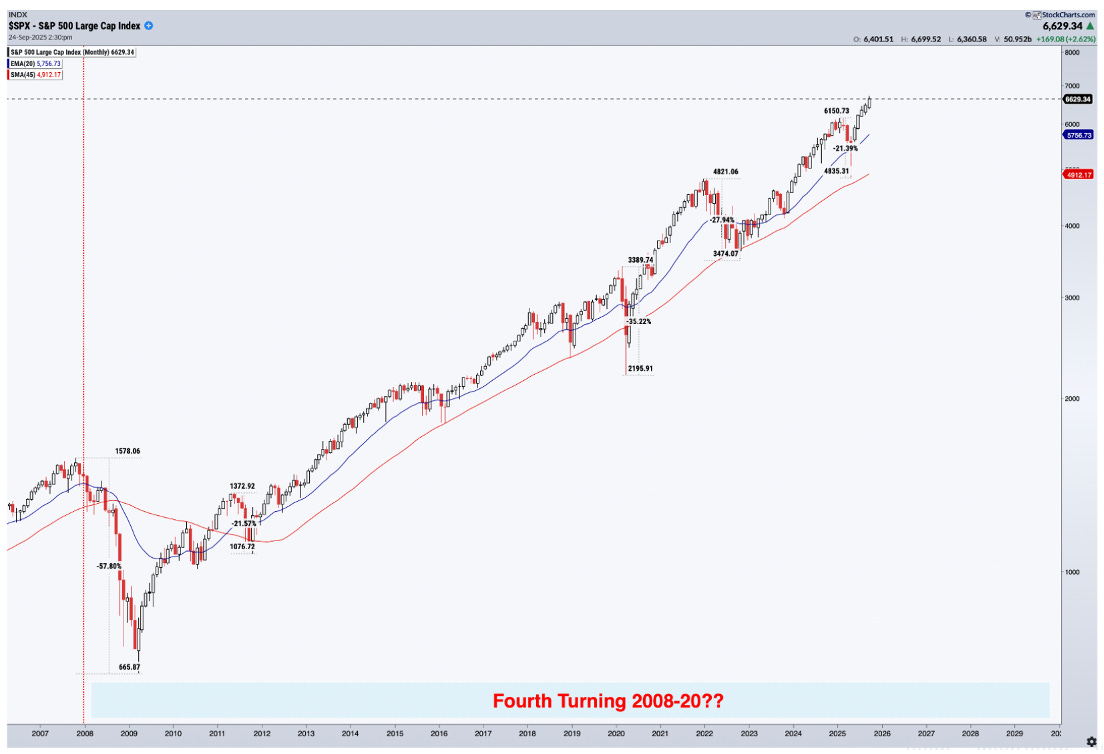

Back in our September 2025 issue, “Pulling a Loomis,” we laid out precisely this case.

We argued that the most dangerous, and therefore most decisive, phase of the Fourth Turning was still ahead of us, and that we were entering that final stretch with record-breaking asset valuations, unresolved excesses, and a financial system that had been stabilized artificially for far too long.

We deliberately used a euphemism back then, but the message was clear: this combination dramatically raises the odds of major repricings.

In that same issue, we also introduced the playbook of a remarkable, yet largely unknown, investor who navigated the last Fourth Turning with exceptional discipline and clarity, emerging from it not just intact, but decisively ahead (Alfred Lee Loomis).

The lesson was not about genius or prediction. It was about process, patience, and positioning when the cycle turns hostile.

Through rigorous work and disciplined implementation of our Investment Process, we fully expect to navigate this Fourth Turning as it reaches its climax, that point of maximum danger, which history also tells us is invariably the point of maximum opportunity.

You might also like reading:

But before we move on to translating all this generational and political analysis into actionable decisions for our Model Portfolio, we want to leave you with one more piece of evidence that this turbulent start to 2026 is about far more than the will or temperament of a single man... even one as disruptive as Donald Trump.

History offers a useful reminder.

In 1917, as the First World War intensified and the global balance of power was being violently reshaped, the United States purchased the Virgin Islands from Denmark.

The rationale was explicit and unapologetically strategic: deny rival powers access to a critical maritime position in the Caribbean and secure control over key shipping lanes near the Panama Canal.

At the time, the move was controversial, framed as opportunistic, and even dismissed by critics as imperialistic... a charge that echoes loudly today.

Yet with the benefit of hindsight, it is now seen as a textbook example of crisis era geopolitics, a great power acting decisively to secure geography, access, and strategic depth as an old order collapsed and a new one was forged.

History, as the saying goes, does not repeat itself. But it does tend to rhyme.

And when everyone looks at today’s events with a sense of disbelief. convinced that “this has never happened before” , it is often because they are staring too closely at the surface, missing the deeper historical pattern quietly reasserting itself.

Our work here is not to pass judgment.

It is to recognize the cycle... and to position our Model Portfolio accordingly.

The Presidential Cycle Playbook

As we’ve just covered in detail, there is now robust evidence supporting the hypothesis that we are indeed living through a Fourth Turning.

Not because of any single event, but because the pattern of events, institutional stress, political radicalization, fiscal dominance, geopolitical assertiveness, aligns remarkably well with how past Fourth Turnings have unfolded.

But there is an important caveat.

Generational cycles are long.

They operate on the scale of decades, not quarters.

And while their internal logic is powerful, their conclusions do not adhere to a precise clock.

In that respect, Neil Howe remains a valuable reference point. In his most recent work and interviews, Howe has reiterated that he expects the current Fourth Turning to resolve sometime in the latter years of this decade, or in the early 2030s at the latest.

That assessment is entirely consistent with the historical duration of prior Crisis eras.

But as we sit here at the beginning of 2026, that still leaves us with a very wide window...

And just as importantly, history also tells us something else: the end of a Fourth Turning, and the bottom in risk assets, do not need to coincide neatly.

Crisis eras often involve multiple waves of stress. False dawns. Relief rallies.

Policy responses that stabilize conditions temporarily, only for deeper imbalances to reassert themselves later.

A new generational cycle can begin socially and politically, even as financial markets are still working through the consequences of excess.

What we do know with much greater confidence is this: Fourth Turnings end with crisis.

And when that crisis unfolds against a backdrop of record or near-record asset valuations, the system’s vulnerability to shocks is materially higher.

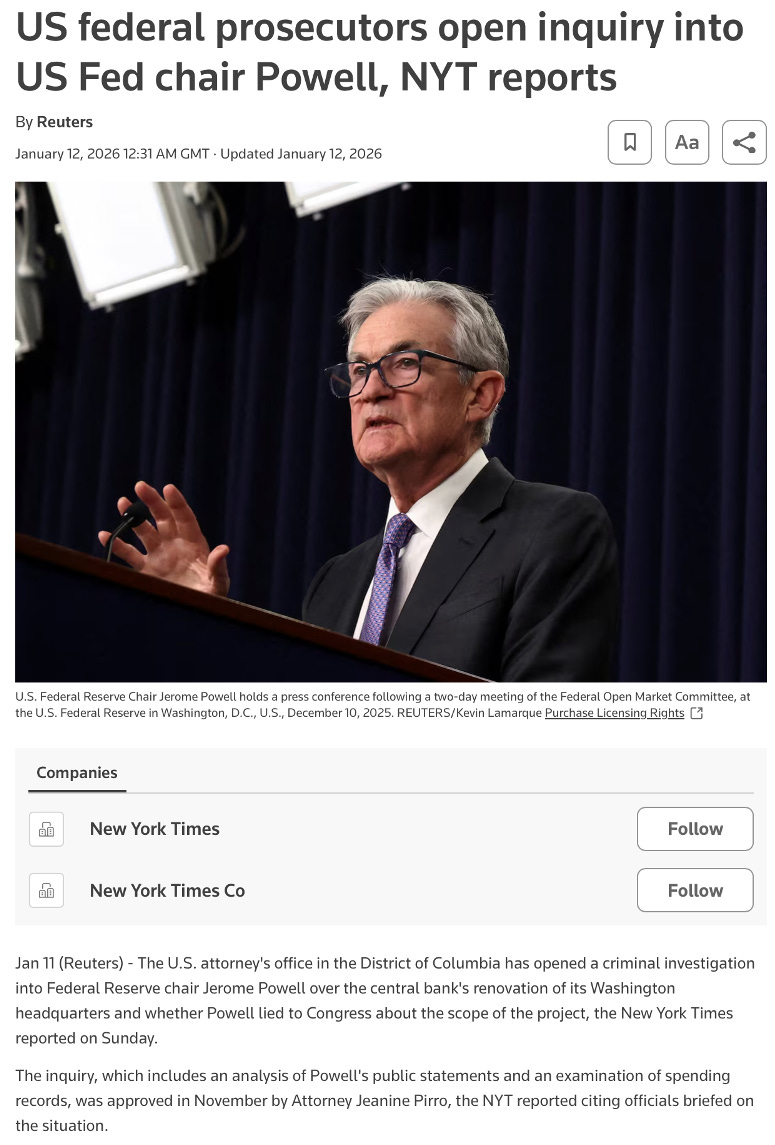

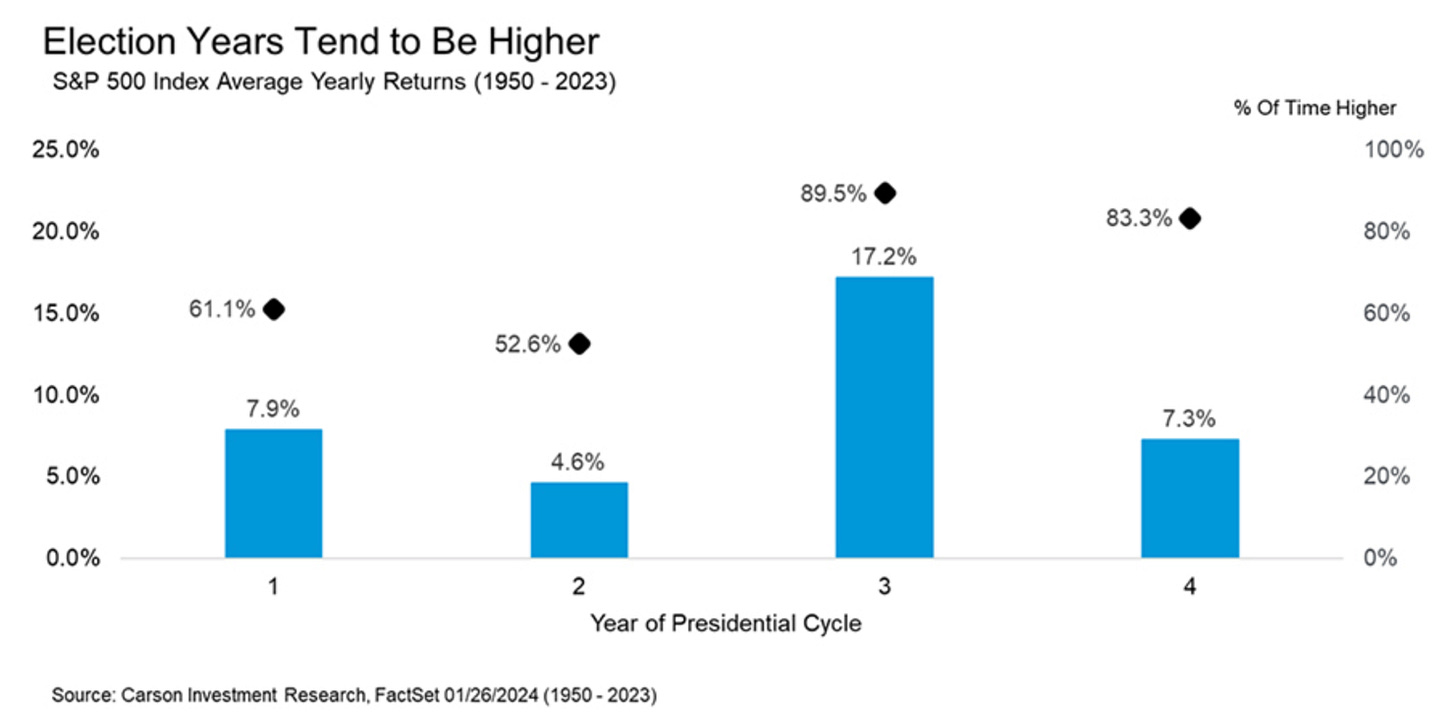

This chart shows the Presidential Cycle in the S&P 500 from 1950 to 2023 — not only the return pattern by year (the blue columns), but also the dots above them showing the percentage of positive years in each phase of the cycle. We’ll break down exactly what it means (and how to use it) in the pages ahead.

In other words, there is far less room for absorption, and far more scope for amplification.

This is not conjecture.

It is precisely the risk highlighted by Neil Howe himself.

In his most recent commentary, Howe has emphasized that this Fourth Turning is historically unusual because it arrived without first purging financial excess.

Previous crisis eras entered their most dangerous phase with markets already broken. This one did not.

The implication is straightforward... and uncomfortable.

When the crisis phase of this cycle ultimately asserts itself in full, the adjustment is unlikely to be orderly.

Elevated valuations, financial repression, and political urgency create the conditions for stress to metastasize, not dissipate.

Markets cease to cushion the shock and instead become a transmission mechanism.

In short, when this crisis arrives the risk is not merely of volatility, but of a vicious structural bear market that reflects years of deferred resolution.

That reality has put our market timing tools on high alert for quite some time now... and we’ve been monitoring them continuously, not episodically.

Which brings us to the next layer of analysis in this issue.

If generational cycles help us understand the regime, we also need tools that help us think about timing within that regime.

Tools that operate on a shorter horizon.

Tools that can help us assess when pressure is most likely to surface, rather than simply acknowledging that it eventually will.

That is why, in this issue, we introduce another cycle, one that is far more compressed, yet no less relevant in 2026: The Presidential Cycle.

Frankly, the narrative is almost too clean.

When we reconcile where we appear to be in the Fourth Turning with the Presidential Cycle and Trump’s approval rating at the start of a midterm year, the analysis comes full circle... and it begins to point uncomfortably toward potential fireworks in financial markets.

But before we go any further, let’s first define what we mean by the Presidential Cycle.

At its core, the Presidential Cycle is a market-timing framework that observes how U.S. equity markets tend to behave over the four years of a presidential term.

While each presidency is different, the pattern that emerges over long periods of time is surprisingly consistent.

And within that pattern, one year stands out... unmistakably.

The second year of the cycle, which coincides with the midterm election year, has historically been the weakest year by a wide margin.

That is precisely the year we are in now.

There are good reasons for this.

Midterm years are when political uncertainty peaks.

Presidents often face the prospect of losing congressional control, legislative agendas stall, and policy risk rises.

At the same time, unpopular but necessary measures like fiscal tightening, regulatory changes, or policy resets, are often pushed through early in a term, before the next presidential election looms.

The result is a toxic mix for markets: elevated uncertainty, reduced political capital, and limited incentive to support asset prices in the short term.

This is not theory...

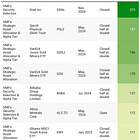

We’ve shown above you robust empirical evidence of this pattern: Total returns of the S&P 500 from 1950 to 2023, broken down by year within the Presidential Cycle. The result is striking.

The second year of the cycle is, by far, the weakest and barely half of all midterm election years finished in positive territory.

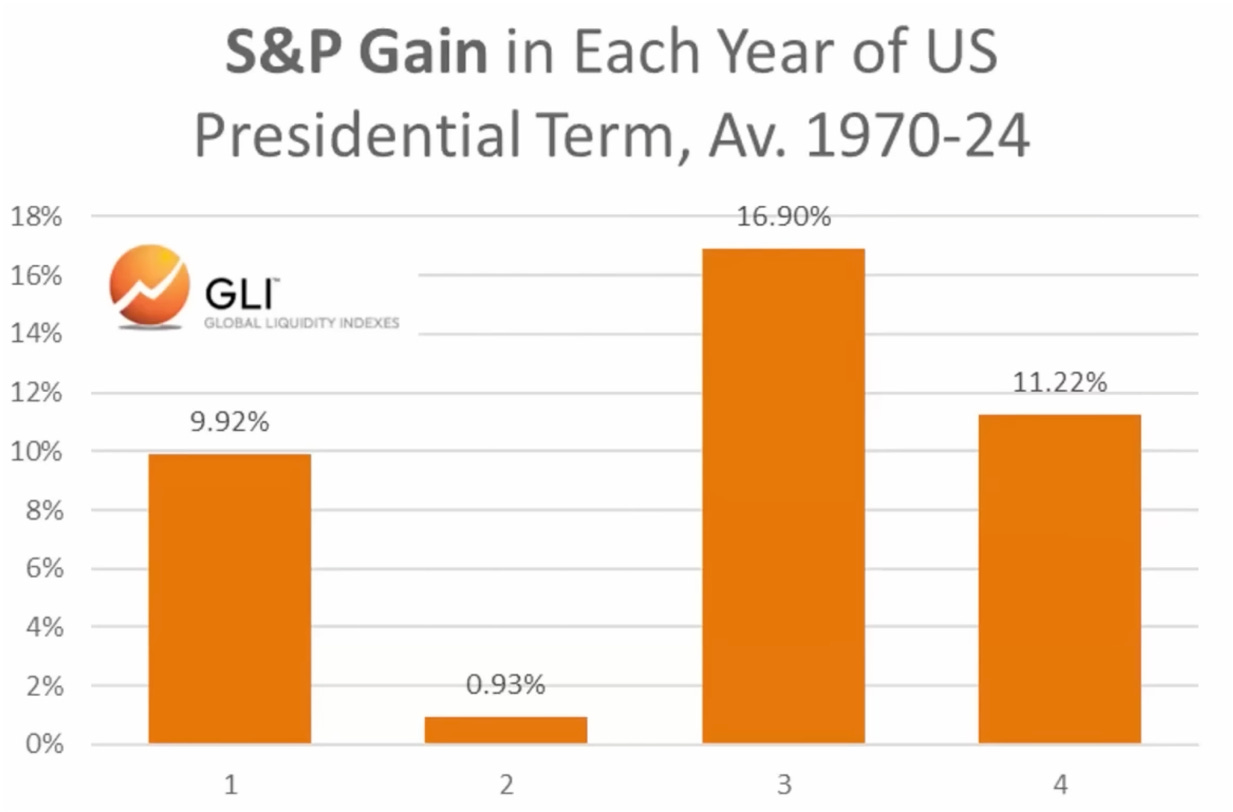

And then from 1970 to 2024.

What stands out immediately is that the Presidential Cycle becomes even more pronounced in this more recent timeframe.

The dispersion between years widens.

The weakness of midterm years becomes clearer. And the strength of the third year becomes even more dominant.

In other words, this is not a fading anomaly from a distant past.

If anything, the Presidential Cycle appears to be gaining strength.

We believe this makes intuitive sense.

We are living in an increasingly politicized world, where policy, markets, and narratives are more tightly intertwined than ever before.

Political incentives matter more.

Headlines move faster.

And uncertainty is priced more aggressively.

The numbers reflect that reality.

Since 1970, CrossBorder Capital estimates that the average return in midterm election years has been a paltry ~1%.

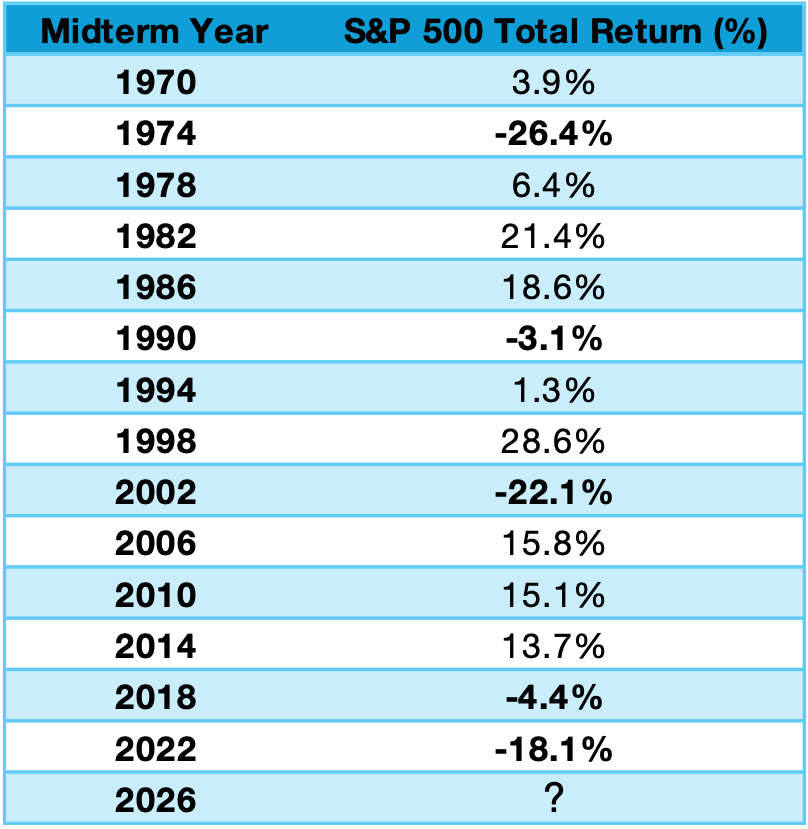

By our own calculations , using S&P 500 total returns (i.e., including dividends, as it should), the average is higher, at ~3.6% based on the table above.

But don’t let that number lull you into complacency.

The distribution is ugly...

Of the 14 midterm years since 1970, five finished negative... and three coincided with outright bear markets.

Two of those, 1974 and 2002, occurred during the late innings of deep, structural drawdowns, with the S&P 500 having suffered peak-to trough declines on the order of ~50%.

In other words, midterm years are not merely “lower return” years… they are the part of the cycle where latent fragility has a habit of showing up all at once.

Does this mean a midterm election year must be negative?

Of course not.

As you can see in the table above, there are also midterm years that finish strongly positive.

And as we’ve been publishing across all our newsletters, there are legitimate reasons to be constructive, even to entertain the possibility of a melt up, particularly in an environment where liquidity is increasing and policymakers, for reasons we’ve discussed at length, have powerful incentives to run the economy hot2.

But that is not the point of the Presidential Cycle.

The point is that this phase of the cycle carries a higher vulnerability to shocks.

It tends to shrink.

And when you reconcile that with where we appear to be in the Fourth Turning… and when you overlay it on a backdrop of record valuations… well, let’s just say this confluence of factors leaves us incredibly vigilant.

One last note about the Presidential Cycle before we move on.

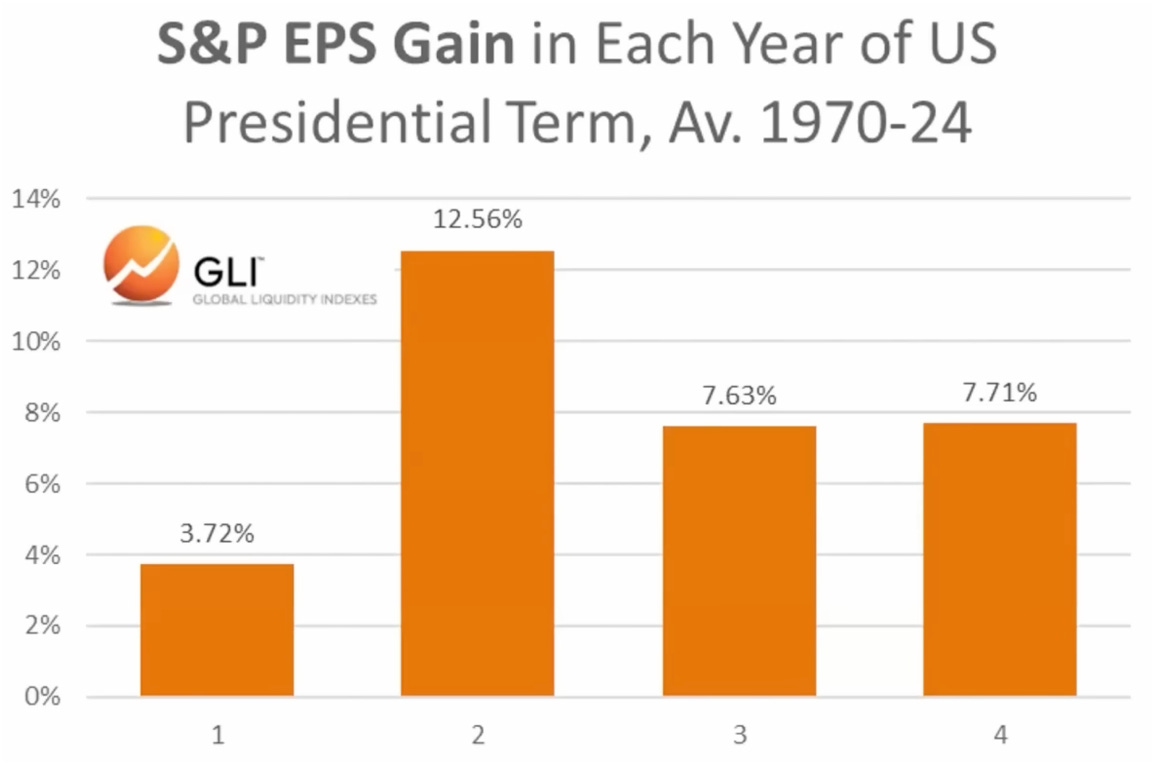

On the chart above - S&P EPS Gain in Each Year of US Presidential Term”, we highlighted a curious mismatch... one that has a high probability of showing up again this year.

Historically, the second year of the Presidential Cycle is often the year where earnings per share grow the fastest.

At first glance, that seems inconsistent.

How can the “worst” year for markets be the year where fundamentals appear strongest?

But when you follow the incentives, and when you look at how policy behaves around elections , it starts to make sense.

Midterm years often become the year where the pain is absorbed, the adjustments are made, and the groundwork is laid.

Strong earnings growth can coexist with weak equity returns when valuations compress, when risk premia rise, or when uncertainty dominates sentiment.

And that compression is precisely what often sets up the following year, the third year, which, as we’ve shown, is historically the strongest year of the entire cycle.

In other words, the second year often does the “dirty work” so the third year can deliver the reward.

Now, it’s time to translate all this cycle work into action.

We’ve just reconciled the very long-term generational cycle, the Fourth Turning. And we’ve now layered in a shorter-term cycle that can meaningfully influence timing and volatility, the Presidential Cycle.

So, now the question becomes simple: what do we do with it?

Thanks for sticking with me through this deep dive. If you value independent, data-driven research that cuts through the noise of this Crisis era, don’t miss our full strategic updates.

The Fourth Turning is the final phase of a recurring generational cycle (a saeculum, roughly 80–100 years) described by Strauss and Howe, in which society moves through four eras: High, Awakening, Unraveling, and then Crisis. The Fourth Turning is that Crisis era: institutions that once felt permanent lose legitimacy, conflicts intensify, and events force rapid decisions. It typically ends with a system-reset moment: a new civic order, new rules, and a rebuilt set of institutions that sets the stage for the next High.

A “Run it Hot” economy is one where policymakers deliberately prioritize growth and employment over inflation discipline — keeping financial conditions easy, encouraging borrowing and spending, and tolerating hotter demand (and often stickier inflation) to sustain momentum. Trump is clearly bent on that outcome because so many of his early moves point in the same direction: pressuring for lower rates, leaning on the housing finance machine to pull mortgage costs down, floating caps that suppress consumer borrowing costs, and generally pushing policy toward maximum short-term economic heat — exactly the kind of stance that plays best heading into a midterm year.