Turning Japanese - Part One: - The Birth of the Intervention Bubble

Japan didn’t just experience a bubble. Japan institutionalized the response to one.

If there’s a single thread running through everything we’ve published lately, it's bubbles.

Not just in stocks. Not just in sectors. But in the way markets think… and in the way policymakers behave. Over the past few months, across our entire product roster, we’ve been circling the same beast from different angles. For instance, last month we went deep on the AI capex boom, a thesis that started as contrarian, then turned mainstream almost overnight. That shift has been breathtakingly fast. Too fast, in fact, for it to feel like a true top.

Real tops don’t arrive with a neat press release and a chorus of agreement. They arrive when everyone is all in and no one feels nervous anymore.

You might also like reading:

We’re not there yet. But the shape of it, the anatomy of it, the timing of it, is still the core theme of this November publication.

Because to understand where this cycle ends, you first have to understand what’s been powering it. And here’s the sober reality: the most dangerous bubble on Earth today isn’t in AI stocks, or crypto, or U.S. megacaps, or even private markets.

It’s in interventionism.

More specifically, it’s in central bank interventionism. For the better part of two decades, central banks have been evolving from referees into full-blown players on the field. They’ve suppressed volatility. They’ve socialized risk. They’ve taught markets, year after year, that drawdowns are temporary and that liquidity will always come back sooner than expected. In doing so, they’ve pumped up what is increasingly an “everything bubble,” floating on a sea of policy support.

But no one took this experiment further than Japan.

Japan was the first to walk down the road that every other major central bank is now traveling. Zero rates before anyone else. Negative rates before most policymakers could even say the words out loud.

Quantitative Easing before it had a name.

Yield-curve control before the West could even imagine it.

While the Fed and ECB were still debating what the limits of intervention might be, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) was already living past them. Call Japan the test lab. The frontier. The warning shot.

You might also like reading:

Because if you want to understand where the global monetary system is headed next, you don’t start in Washington or Frankfurt.

You start in Tokyo.

That’s why this issue is devoted to Japan’s 40-year arc, from its late-1980s equity and real-estate mania (the kind of bubble so extreme that people seriously claimed the Imperial Palace was worth more than all of California), to the spectacular collapse, to the deflationary hangover that lasted decades… and finally to the most ambitious experiment in monetary and fiscal intervention ever attempted by a modern nation.

Japan didn’t just experience a bubble.

Japan institutionalized the response to one.

And the rest of the world, especially after 2008, has been quietly turning Japanese ever since. Once you see Japan’s story clearly, today’s global market picture snaps into focus. You start to recognize the deeper current beneath all the headlines: the great, global debasement trade. A regime where debt must be rolled, liquidity must be injected, and currencies must be sacrificed... not because policymakers want to,but because the system can no longer function without it.

So, we’re going to walk through Japan’s journey in depth. Not as history or for history’s sake. But because Japan is a roadmap. A case study that lets us understand what the rest of the world is doing now… and what it may be forced to do next. And once that dynamic is understood, we’ll bring it home to the setup in front of us as we enter the final stretch of 2025.

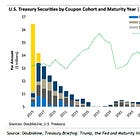

In the United States, Quantitative Tightening (QT) is about to end. The Treasury General Account (TGA) looks poised to be drained. The market is increasingly pricing a renewed wave of rate cuts starting in December. In other words, the pieces are lining up for what could be the final liquidity push of this cycle.

You might also like reading:

Is that push about to begin?

And if it is, what does it mean for risk assets? For inflation expectations? For the debasement trade? And for our Alpha Tier Model Portfolio?

“Turning Japanese” is Part 1 of our November Alpha Tier. If you want to access the full content inc. the actual playbook: tickers, weights, and our month-by-month moves get the full issue now. Members see every dial we turn before we publish Part 2 next week.

Join Alpha Tier @ VMF Research.

The Birth of the Intervention Bubble

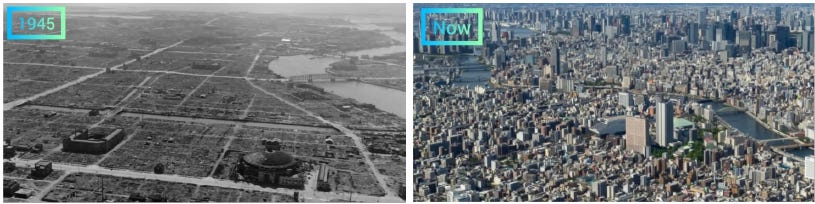

In 1945, Japan was in ruins.

Two cities erased by atomic fire. Industrial capacity shattered. Millions homeless. Hunger everywhere. If you had stood in the streets of Tokyo after the surrender, amid the ash and the silence, you wouldn’t have seen a future economic superpower.

You would have seen a country trying to survive one more winter.

And yet, in one of history’s great turnarounds, Japan rebuilt itself faster, and more completely, than anyone thought possible. During the 1950s and 1960s, the country went through what historians now call the “Japanese economic miracle.” Growth routinely ran at high-single to double digits. Japan became the factory floor of the developed world, exporting cars, electronics, steel, shipbuilding, you name it.

Household savings poured into banks, banks poured money into industry, and the state, through MITI and the keiretsu system, helped coordinate an export juggernaut.

By the late 1970s, Japan had risen to become the world’s second largest economy.

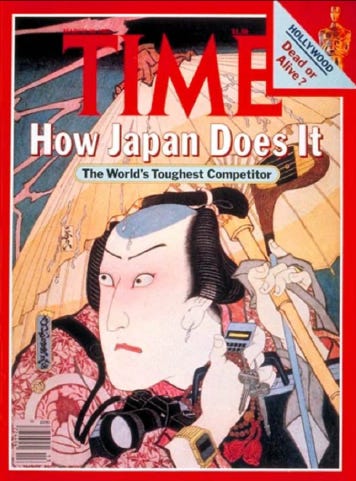

That machine was so powerful that by the early 1980s, Americans were openly worried Japan would out-produce them, out-innovate them, and eventually out own them.

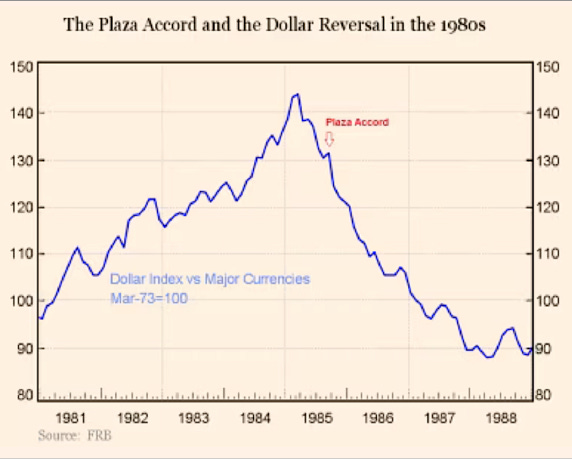

Then came the Plaza Accord1 in 1985.

The U.S. forced a coordinated revaluation to weaken the dollar and strengthen the yen. The yen surged. Japan’s export engine suddenly looked vulnerable. And Tokyo’s leadership panicked: to cushion the shock, policymakers leaned hard on stimulus and easy money. In hindsight, that decision didn’t just soften a slowdown.

It lit the fuse on the greatest asset bubble of the modern era.

By the second half of the decade, Japan wasn’t merely growing. It was levitating. Stocks and real estate climbed in a straight line, not because productivity was exploding, but because credit was.

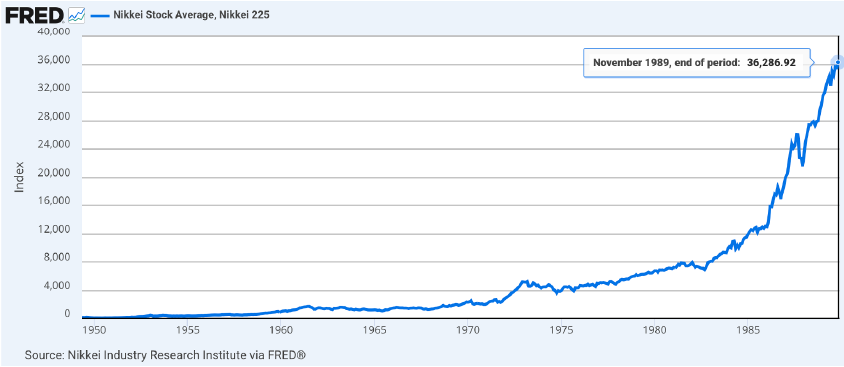

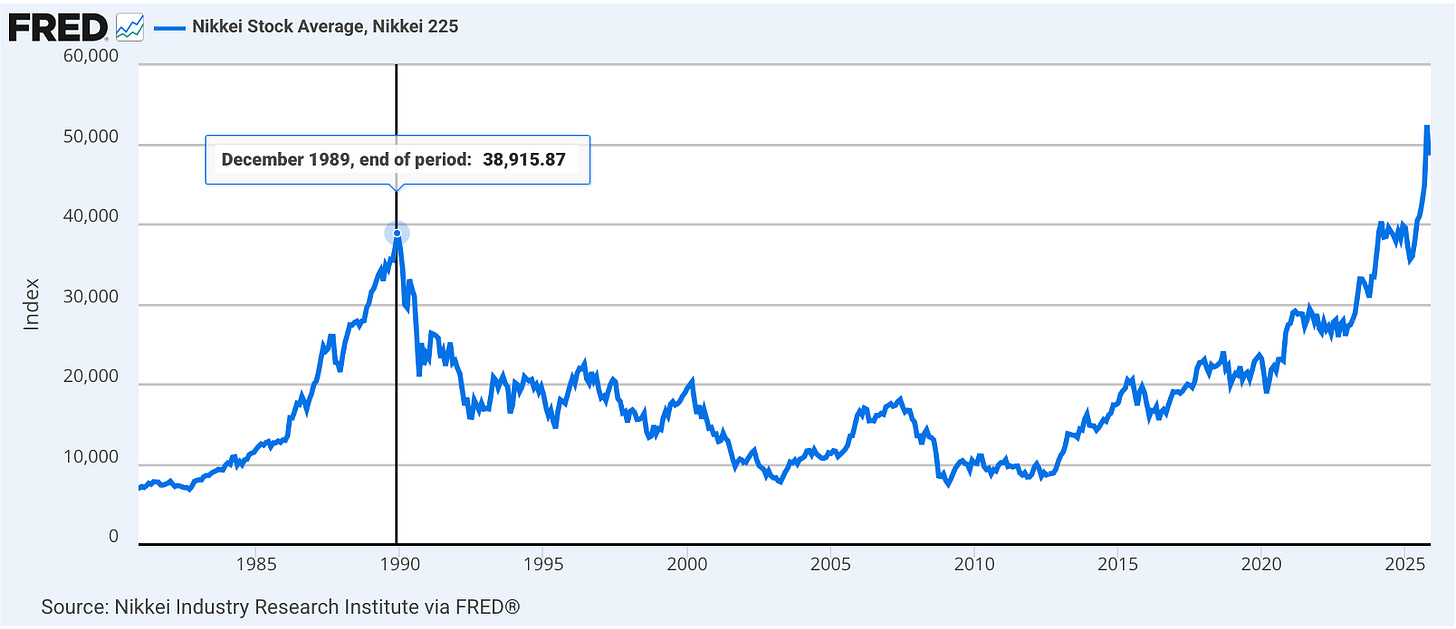

The Nikkei rose from roughly 6,867 in 1980 to 38,915 by the end of 1989. Every year of the decade was up. The final stretch was pure mania: +40% in 1988 and another +29% in 1989. At the peak, Japanese equities represented about 45% of global market capitalization, nearly half the world’s stock market in one country.

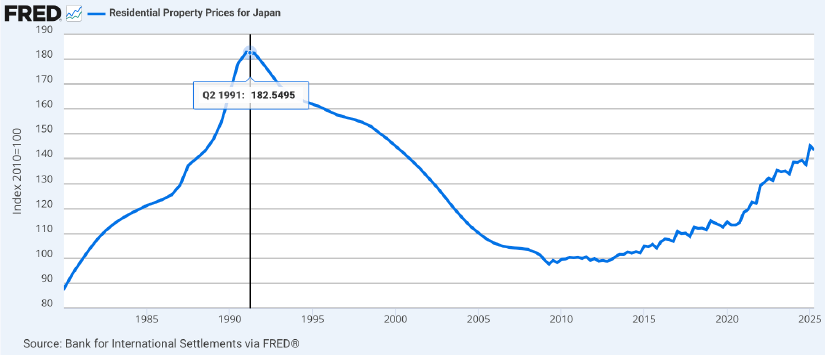

And Japan’s property market makes today’s bubbles look polite.

Tokyo land became a national obsession. Bankers, office clerks, taxi drivers, everyone talked about property like it was a one-way ticket to lifetime wealth. In the Ginza district, a single square meter sold for around ¥32 million (about $230,000 at the time).

The most famous comparison became a sort of folk theorem of the age: the land under the Imperial Palace in Tokyo (just 3.4 km²) was said to be worth more than all the real estate in California.

People repeated it so often it stopped sounding crazy.

That’s how bubbles work: the absurd becomes normal through repetition. Money wasn’t just flowing. It was flaunting itself.

Golf club memberships traded for the price of luxury homes. Art auctions set records weekly. Department stores sold out of imported European handbags as fast as they could stock them. Executives took same-day flights across the country just to have lunch. And the public mood shifted from proud to invincible.

Japan wasn’t catching up anymore. Japan was taking over.

And nowhere was that confidence louder than on the corporate front.

Japanese companies were drowning in cheap capital and rising collateral values. So, they did what every empire does at its peak: they started buying trophies abroad, especially in the United States. In 1989, Mitsubishi Estate bought Rockefeller Center in New York, a deal that felt symbolic even then. Japanese capital acquiring one of America’s most iconic business monuments.

The same year, Sony bought Columbia Pictures for $3.4 billion, effectively planting the Japanese flag in Hollywood. Japanese firms bought Pebble Beach. Bridgestone bought Firestone. A stream of American brands, real estate, and industrial assets suddenly had Japanese owners.

In the U.S., people began to ask (half joking, half terrified) whether America was becoming a subsidiary of Japan Inc.

This wasn’t just expansion. It was a statement. The message was: we’re not a postwar miracle anymore, we’re the new center of gravity. And inside Japan, that message became self-reinforcing. Rising prices justified more lending. More lending justified higher prices. Corporate balance sheets looked stronger not because businesses were earning more, but because their real-estate holdings were worth more every month.

The value of land became the foundation for leverage, speculation, and what felt like a permanent national ascent.

Of course, none of it was permanent.

The chart below shows the Nikkei’s parabolic rise in the 1980s. Note how the slope steepens after the Plaza Accord, as monetary and fiscal stimulus went into overdrive to cushion the impact of the yen’s sharp appreciation.

But at the time, it was impossible to imagine anything else.

That’s the real signature of a bubble.

It doesn’t feel risky. It feels inevitable. Every story you hear is a confirmation. Every chart is a promise. Every skeptic looks like a bitter outsider who just doesn’t get it.

And that was Japan in 1989: euphoric, over-levered, world-conquering, and standing on the edge of a trapdoor it didn’t know existed.

However, every great bubble ends the same way.

Not with a gentle cooling. Not with a “soft landing.” But with something snapping that everyone assumed could never break. For Japan, that snap came in the early 1990s.

The Nikkei rolled over in 1990. By mid-1992, equity prices were down roughly 60% from the peak. Land prices, which everyone had treated as “can only go up” collateral, started their own long slide a year later. The charts that had soared in a straight line up now went in a straight line down.

Years of speculative excess, built on a shaky foundation of leverage and property, suddenly ran into the only thing that ever really matters: reality.

Under the surface, the damage was even worse than it looked.

Property loans at non-bank lenders (the famous jusen housing loan companies and other shadow arms of the big banks) had exploded from roughly ¥22 trillion in 1985 to about ¥80 trillion by 1989. These outfits had been shoveling money into real estate at the top of the market. When land prices cracked, those loans didn’t just go “bad.” They turned radioactive. They became non-performing in a system that was never built to admit losses on that scale.

And that’s where the story shifts from a normal bust, to something much darker.

Because the real story of Japan’s “Lost Decades” isn’t just about a bubble popping.

It’s about what policymakers did next.

At first, Tokyo didn’t want a crisis. It wanted time. And that, in effect, was the beginning of the great Intervention Bubble. Big Japanese banks were stuffed with bad loans, not only directly on their books, but also indirectly via their non-bank subsidiaries and affiliated jusen. If regulators had forced an honest mark-to-market in 1991–1992, several of these institutions would have been insolvent on the spot.

Instead, the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Japan chose another path: forbearance.

Banks were quietly encouraged to “extend and pretend,” roll over bad loans, restructure terms, keep the borrowers alive on paper. New accounting rules and supervisory guidelines gave them room to avoid recognizing losses immediately.

Depositors were reassured their money was safe. The idea was simple: if you give the system time, growth will come back, asset prices will stabilize, and the problem will shrink.

But... time didn’t fix it.

Enjoying the reading?

“Turning Japanese” is Part 1 of our November Alpha Tier. If you want to access the full content inc. the actual playbook: tickers, weights, and our month-by-month moves get the full issue now. Members see every dial we turn before we publish Part 2 next week.

Join Alpha Tier @ VMF Research.

As the 1990s progressed, it became clear that the rot was spreading, not shrinking.

Bad loans were like dry rot in the foundation of a house... invisible from the street, but steadily eating through the structure. Credit creation slowed because banks didn’t want to admit losses and raise fresh capital. They stopped taking risk. They stopped lending.

And the real economy suffocated.

The first visible crack came in the jusen crisis. Those housing loan companies, created by the major banks and agricultural lenders to funnel credit into real estate, were now utterly insolvent. By the mid-1990s, the government could no longer pretend they’d grow their way out.

In 1995–1996, Tokyo cobbled together a bailout package to wind down seven major jusen firms. Taxpayer money was used to plug the hole, along with contributions from the large founding banks and agricultural institutions that had fed them business.

The politics were toxic. Farmers were furious. Voters were furious. The idea that taxpayer funds would be used to clean up the mess of reckless lenders became a national scandal.

But here’s the key point: even that messy, controversial jusen rescue was just the opening act. The real bank bailouts came later, and they were much bigger. By 1997–1998, Japan was in a full-blown financial crisis. Hokkaido Takushoku Bank failed. Yamaichi Securities (one of Japan’s “Big Four” brokers) collapsed. Confidence in the system wavered. At that point, Tokyo finally did what it had been avoiding since 1990: it moved from quiet forbearance to overt recapitalization.

New laws were passed to allow the state to inject capital directly into banks. Temporary schemes were set up under the Deposit Insurance Corporation. Asset management companies were created and consolidated (culminating in the Resolution and Collection Corporation in 1998) to buy bad loans from failing institutions and work them out over time. Between 1992 and 2000, the total cost of dealing with non-performing loans (write-offs by banks, public capital injections, deposit insurance payouts) reached on the order of ¥80–¥90 trillion, roughly 17% of Japan’s GDP.

Think about that: almost a fifth of the country’s annual output, consumed by cleaning up the aftermath of the boom. Or, put another way, that was the size of the intervention up to that point. because, as you’ll see ahead, it only gets bigger from there.

Japan did, in the end, avoid an American-style “Lehman moment.” There was no single day when the entire system flatlined. But the bill for slow-motion rescue? Enormous.

The result was something worse than a conventional crisis.

And thus began Japan’s infamous “Lost Decade” which, as we now know, stretched into something closer to three decades.

Throughout the 1990s, growth sagged. Real GDP barely crawled forward. The stock market never came close to its old highs. Land prices kept leaking lower. Deflation, a concept most investors still don’t fully appreciate, quietly took hold.

Consumer prices drifted down. Wages stagnated. Asset values bled away year after year. By the end of the decade, Japan’s real GDP was actually lower than it had been at the start of the 1990s.

A Great Depression-style collapse had been averted, yes. But what replaced it was a long, grey tunnel of economic anemia.

And that economic anemia didn’t just hit portfolios. It seeped into the country’s demographics. When you live for years in a world where prices don’t rise, promotions are rare, and the future feels smaller than the past, you don’t rush to buy a home, get married, or have children. You delay. You scale down. You decide ”later” is safer than “more.” Over time, that mentality eats into birth rates. The population ages. The base of young, risk-taking workers shrinks, while the ranks of retirees grow.

Japan’s malaise didn’t just slow growth, it helped lock in the demographic time bomb the country is still defusing today. The term “Japanification” entered the global lexicon to describe this mix of chronic low growth, persistent disinflation or outright deflation, and a banking system that never quite healed. An entire generation of Japanese citizens grew up in an environment where prices didn’t rise, wages didn’t move, and the future didn’t look brighter than the past. People adapted by cutting spending, hoarding cash, and lowering their expectations.

Enjoying the reading?

“Turning Japanese” is Part 1 of our November Alpha Tier. If you want to access the full content inc. the actual playbook: tickers, weights, and our month-by-month moves get the full issue now. Members see every dial we turn before we publish Part 2 next week.

Join Alpha Tier @ VMF Research.

That mentality, more than any one data point, is what defines a lost decade.

Policymakers didn’t sit on their hands. Throughout the 1990s, Tokyo rolled out massive fiscal stimulus packages: roads, bridges, tunnels, dams, airports, public works of every kind. Concrete became a policy tool. Each new program was sold as the one that would finally “jump-start” growth… the bridge that would unlock regional development, the highway that would catalyze commerce, the public project that would jolt the economy back to life.

Each one also added more public debt.

The sugar highs were always temporary. As soon as the stimulus faded, the same underlying problems reappeared: a wounded banking system, cautious consumers, entrenched deflationary expectations, and a government that increasingly reached for the next round of spending, rather than confronting the core disease.

But it was on the monetary policy front that this intervention wave really went into overdrive.

Fiscal bailouts and public-works binges were the opening chapters. The real story, the one that matters for the “everything bubble” we’re living through today, is what happened when the Bank of Japan decided that price discovery itself was the problem.

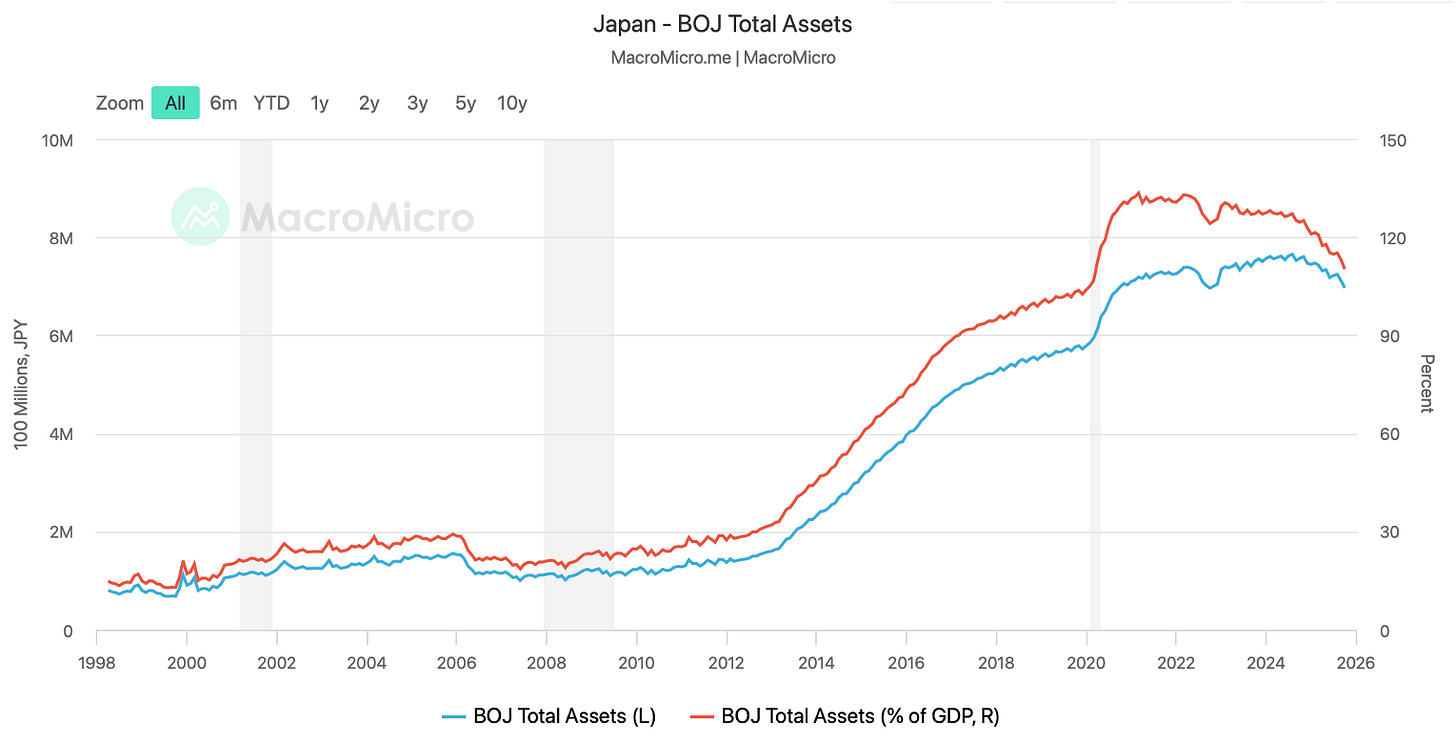

Faced with stubborn deflation and an economy that refused to wake up, Japan entered an era of remarkable central bank intervention and relentless public debt accumulation. As the 2000s and 2010s progressed, the BoJ kept pushing the envelope of monetary policy further than any other major central bank.

First came ZIRP2. After the 1990s grinding slump, the BoJ cut its policy rate all the way to zero by 1999. That was supposed to be extraordinary and temporary.

It became the new baseline. When zero still wasn’t enough to break deflation, the BoJ crossed the next line in 2001 and launched the world’s first modern experiment with Quantitative Easing (QE), targeting the size of bank reserves and using large scale purchases of Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) as the main tool.

Meanwhile, something important was happening on the balance-sheet front. Corporate Japan, burned by the 1990s, spent the 2000s slowly deleveraging, repairing its balance sheets and hoarding cash instead of piling on more debt.

By the mid-2000s, firms had largely completed this process. Households, too, were cautious. The private sector stopped leveraging up.

But the debt didn’t disappear. It moved. The state stepped in. Year after year, stimulus package after stimulus package, deficits piled up. As one comparative study of post-crisis debt dynamics put it bluntly: in Japan, virtually all of the increase in debt came from the public side. In other words, the debt burden migrated from private balance sheets to the government’s balance sheet.

And all the while, the BOJ kept building new tools.

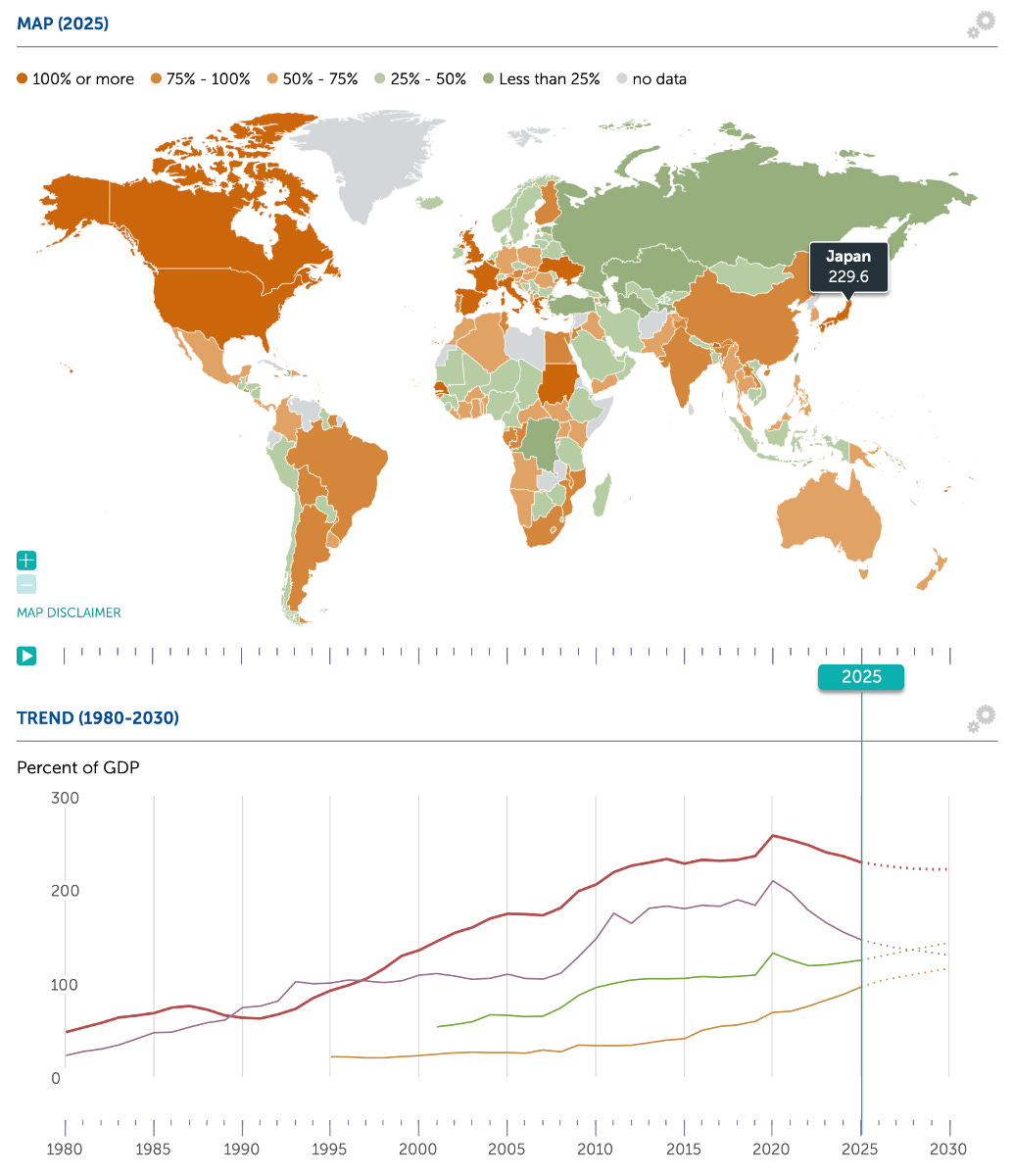

The chart on the side shows Government Debt-to-GDP ratios by country and, as you can see, Japan is the most indebted major economy in the world on this metric.

After a pause in the mid-2000s, quantitative easing returned with a vengeance in the 2010s. Under Governor Haruhiko Kuroda and Prime Minister Shinzō Abe’s economic agenda (Abenomics) the BoJ in 2013 rolled out Quantitative and Qualitative Easing (QQE), a program explicitly designed to finally hit a 2% inflation target.

Short rates were already at zero, so the BoJ went big on everything else: long-term JGBs, risk assets, and what it euphemistically called “qualitative” measures... in plain English, buying things central banks weren’t supposed to buy.

Under QQE, the BoJ didn’t just buy government bonds. It started buying equity ETFs in size. It bought J-REITs (listed real-estate trusts). It bought corporate bonds. By the late 2010s, the BOJ was the pacesetter among global central banks when it came to purchasing non-government financial assets. It was the first major centralbank to openly admit it was buying stock-market index products as a policy tool.

The BoJ’s balance sheet exploded relative to the size of the economy, eventually surpassing Japan’s entire GDP.

Then they went even further.

In 2016, the BoJ pushed its policy rate below zero, introducing a negative interest rate of -0.1% on part of the banking system’s reserves. That still wasn’t enough. So, the same year, they unveiled what might be the single most radical tool in modern central banking: yield-curve control (YCC).

The BoJ didn’t just set the overnight rate. It capped the 10-year JGB yield around 0%, promising to buy as many bonds as necessary to keep long-term borrowing costs pinned near zero.

Zero rates. Negative rates. QE. QQE. ETF buying. REIT buying. Yield-curve control.

If QE and ZIRP were the “unconventional” tools after 2008 in the West, in Japan they became conventional. And every time the old tool stopped working, the BoJ built a new one.

The cumulative effect of decades of fiscal and monetary intervention was predictable: public debt went vertical.

Japan’s gross government debt blew through one quadrillion yen in the early 2010s and kept climbing. By 2024–2025, it hovered around 220–250% of GDP, the highest ratio in the world.

Crucially, around 90% of that debt is held domestically, by Japanese banks, insurers, pension funds, and, increasingly, by the BoJ itself. As of recent years, the BoJ has owned roughly half of the entire JGB market.

Read that again.

The central bank owns about half of its own government’s bond market.

In plain language, the BOJ has been buying the government’s debt with newly created money, keeping yields suppressed and funding costs artificially low. In most countries, that would be called debt monetization and would trigger panic. In Japan, it’s been branded as “necessary policy innovation.”

Critics call it something else: a kind of financial alchemy that, to many, now feels almost permanent, but we’ve seen how these perceptions of permanence have ended before.

For decades, Japan has been defying the textbooks.

Despite massive interventions and money printing, deflation and very low inflation have persisted. The yen, far from collapsing, often acts as a safe-haven currency. The thing investors run toward whenever the world hits a risk-off moment.

Why? Because Japan has a chronic current-account surplus, and because of one of the most powerful forces in global markets that most investors barely think about:

The yen carry trade.

For years, speculators and institutions around the world have been borrowing in yen at ultra-low rates and plowing the proceeds into higher-yielding assets elsewhere.

It works beautifully, until it doesn’t.

Every time volatility spikes and those carrytrades have to be unwound, speculators are forced to buy back yen to repay their funding.

The result?

The currency of the most aggressive money-printer on Earth often strengthens right when theory says it should fall.

This apparent contradiction, unprecedented monetary expansion without runaway inflation, a serial money-printer whose currency rallies in panics, is exactly what seduces other central banks into “turning Japanese.”

If Japan can print this much, suppress yields this hard, and still avoid inflation and a currency crisis, why can’t everyone else?

But the side effects have been enormous:

Free markets in JGBs? Distorted by a single buyer with a printing press.

True price discovery in Japanese equities? Warped by a central bank that, at one point, was among the largest holders of domestic ETFs.

Bank profitability? Crushed for years under zero and negative rates.

Government discipline? Eroded by the knowledge that any deficit can be financed at near-zero cost as long as the BOJ keeps showing up in the bond market.

And here’s the crucial point:

It’s precisely because deflation and ultra-low inflation persisted, and because interest rates stayed pinned near zero or below, that Tokyo was able to keep scaling these interventions without tripping the classic alarm bells.

No Bond Vigilantes. No inflation panic.

No currency collapse. Just more debt, more QE, more yield-curve control… and more faith that “if Japan can get away with it, so can we.”

Japan chose the path of gargantuan interventions and status-quo preservation over any cathartic reckoning.

It has so far avoided a sudden financial collapse, no 1929 Crash, no Lehman moment. But at the cost of enfeebling its economy, entrenching deflationary psychology, and building the largest public-debt mountain in modern history on top of the most aggressive central bank balance sheet the world has ever seen.

This is the Intervention Bubble in its purest form.

Its biggest expression, pushed the farthest, for the longest.

And, as we’ll see, the rest of the world has been following Japan down this path ever since 2008.

Next week, we’ll unpack why this analysis matters so much right now, as Western central banks, led by the Fed, edge ever closer to the same limits Japan has been testing for 30 years.

The Plaza Accord was a coordinated agreement signed in September 1985 at New York’s Plaza Hotel by the G5 nations at the time: the United States, Japan, West Germany, France and the United Kingdom. Its core objective was to engineer a controlled depreciation of the overvalued U.S. dollar and a corresponding appreciation of the Japanese yen and German deutsche mark. Policymakers agreed to coordinated foreign-exchange interventions and aligned policy signals to push the dollar lower, in order to reduce U.S. trade deficits and ease mounting trade tensions. For Japan, the Plaza Accord was a critical turning point: the sharp post-Accord appreciation of the yen squeezed exporters and helped trigger the aggressive monetary easing that later fueled the country’s late-1980s asset bubble.

ZIRP, NIRP and QE are shorthand for the three great tools of modern monetary experimentation. ZIRP (Zero Interest Rate Policy) is when a central bank pushes its policy rate effectively to 0% in order to stimulate credit and risk-taking once conventional easing has been exhausted; the Bank of Japan was the first major central bank to adopt ZIRP in the late 1990s. QE (Quantitative Easing) goes further, with the central bank creating reserves to buy large quantities of government bonds and other securities, compressing longer-term yields and flooding the system with liquidity; again, the BoJ was the pioneer here, launching its first QE programme in 2001, years before the Fed and the ECB copied the playbook after 2008. NIRP (Negative Interest Rate Policy) is the more extreme step of setting some policy or deposit rates below 0%, effectively charging banks to hold excess reserves; the ECB moved first into negative rates in 2014 and the BoJ followed in 2016, making Japan not the inventor of NIRP but the only major central bank to combine, over time, ZIRP, QE, NIRP and later yield-curve control in one continuous experiment.

Brilliant! The way it unpacks history, market dynamics, and underlying trends with such precision is outstanding... a truly exceptional lookthrough!